Fundamentals Of Data Engineering

These are my notes from the book Fundamentals Of Data Engineering.

Although you can access the content through the github page, this is a served with mkdocs-material 💕

Why ? 🤔

This is an amazing book for everyone involved in data.

By the end of the book you'll be better equipped to:

- Understand how data engineering fits into roles like data scientist, analyst, or engineer

- Cut through hype to choose the right tools, architectures, and processes

- Design robust systems using the data engineering lifecycle

- Apply data engineering principles in your day-to-day work

- Solve data problems using a lifecycle-based framework

Which is a pretty good deal. 🎉

I thought, I can share some of my highlights from it. If you want to discover more about any of the topics, please check out the book.

If you’re interested in the book, you can purchase one. It was previously available via Redpanda, but the free copy is no longer offered. Now, that link redirects to a guide, which is still useful.

The Structure 🔨

The book consists of 3 parts, made up of 11 chapters and 2 appendices.

Here is the tree of the book.

And the following are my notes, following this structure.

Fundamentals of Data Engineering

├── Part 1 – Foundation and Building Blocks

│ ├── 1. Data Engineering Described

│ ├── 2. The Data Engineering Lifecycle

│ ├── 3. Designing Good Data Architecture

│ └── 4. Choosing Technologies Across the Data Engineering Lifecycle

├── Part 2 – The Data Engineering Lifecycle in Depth

│ ├── 5. Data Generation in Source Systems

│ ├── 6. Storage

│ ├── 7. Ingestion

│ ├── 8. Orchestration

│ └── 9. Queries, Modeling, and Transformation

└── Part 3 – Security, Privacy, and the Future of Data Engineering

├── 10. Security and Privacy

└── 11. The Future of Data Engineering

Part 1 – Foundation and Building Blocks 🏂

Let's discover the land of data together.

1. Data Engineering Described

Let's clarify why we are here.

Definition of Data Engineer 🤨

Who is a data engineer? What do they do?

Here is Joe's and Matt's definition:

Data engineering is the development, implementation, and maintenance of systems and processes that take in raw data and produce high-quality, consistent information that supports downstream use cases, such as analysis and machine learning.

Data engineering is the intersection of security, data management, DataOps, data architecture, orchestration, and software engineering. A data engineer manages the data engineering lifecycle, beginning with getting data from source systems and ending with serving data for use cases, such as analysis or machine learning.

If you do not understand these definitions fully, don't worry. 💕

Throughout the book, we will unpack this definition.

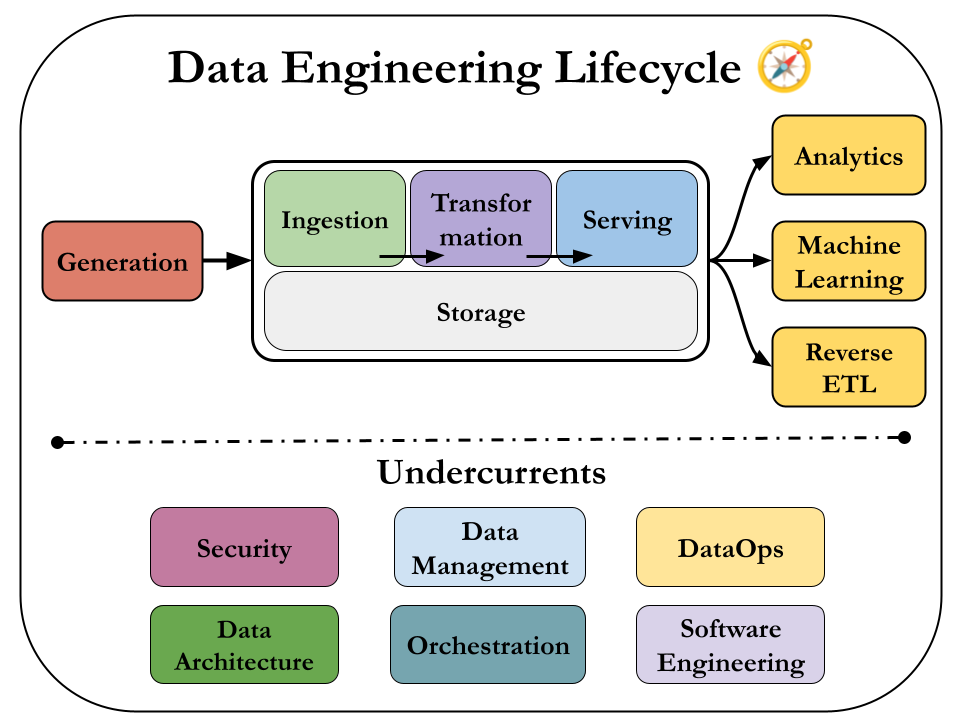

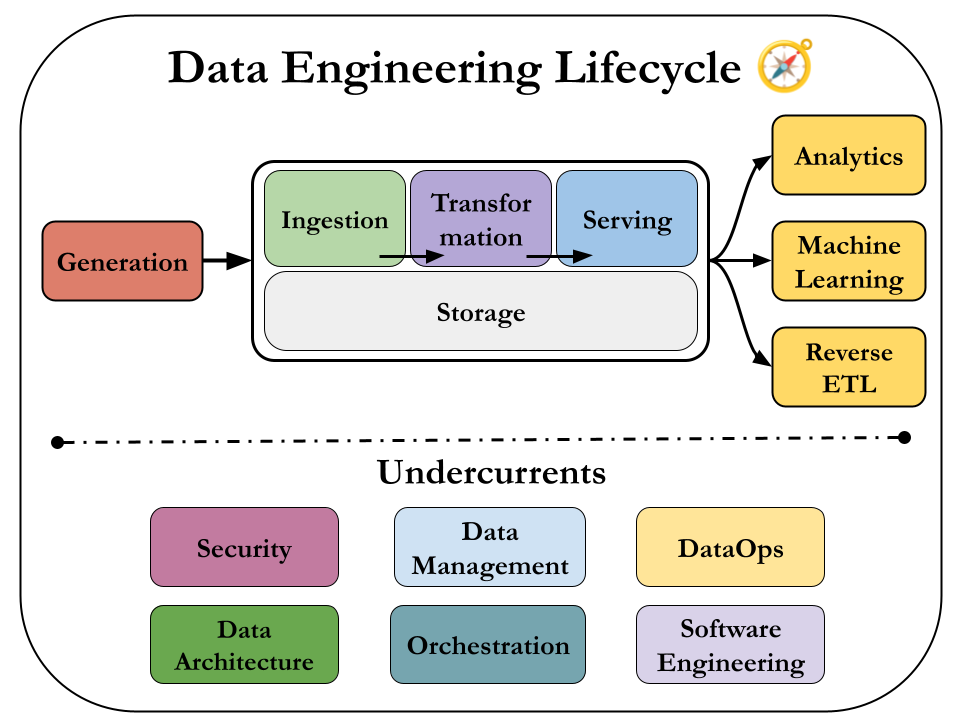

Data Engineering Lifecycle

The book is centered around an idea called the data engineering lifecycle, which gives data engineers the holistic context to view their role.

So we'll to dive deep in these 5 stages:

- Generation

- Storage

- Ingestion

- Transformation

- Serving

and consider the undercurrents of them.

I believe this is a fantastic way to see the field. It's free from any single technology and it helps us focus the end goal. 🥳

Evolution of the Data Engineer

This bit gives us a history for the Data Engineering field.

Most important points are:

- The birth of Data Warehousing (1989 - Bill Inmon) - first age of scalable analytics.

- Commodity hardware—such as servers, RAM and disks becoming cheaper.

- Distributed computation and storage on massive computing clusters becoming mainstream at a vast scale.

- Google File System and Apache Hadoop

- Cloud Compute and Storage becoming popular on AWS, Google Cloud and Microsoft Azure.

- Open source big data tools are rapidly spreading.

Data engineers managing the data engineering lifecycle have better tools and techniques than ever before. All we have to do is to master them. 😌

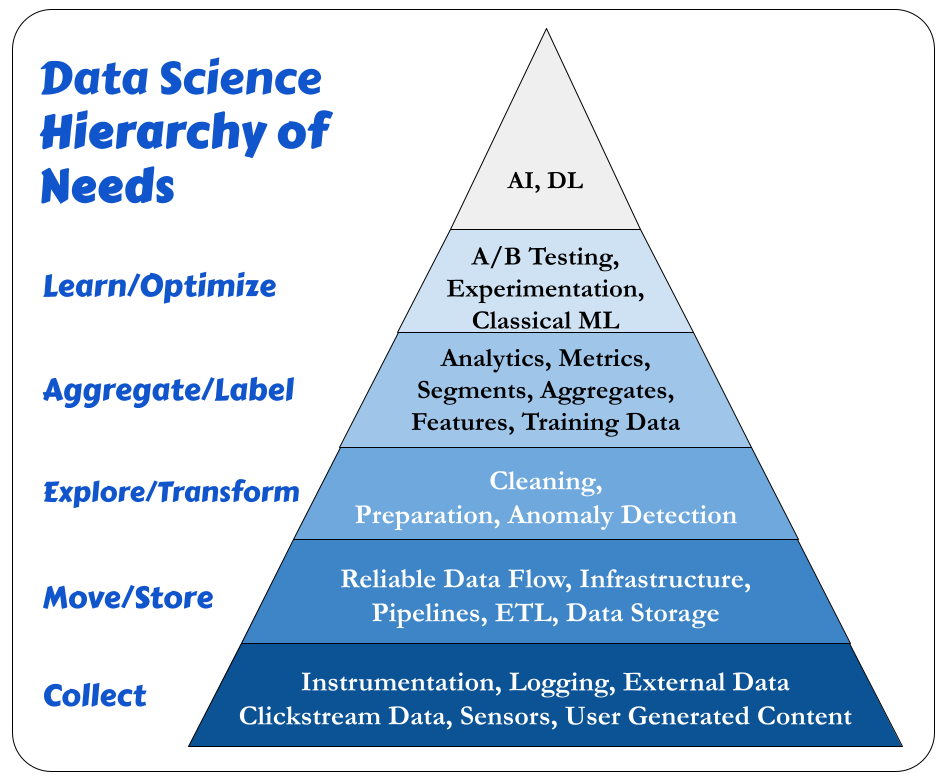

Data Hierarchy Of Needs

Another crucial idea to understand is the Data Hierarchy Of Needs:

Special thanks to Monica Rogati.

We need a solid foundation for effective AI and ML.

Here is how I interpret this image:

Collect:

We gather the raw inputs that fuel all downstream data work.

Instrumentation

Instrumentation means embedding code or tools into applications & systems to collect data about usage or performance.

Examples:

- Adding tracking code (e.g., Google Analytics) to a website

- Emitting events like

button_clickorcheckout_start - Measuring server response times

📌 Goal: Make sure data is being captured from the start.

Logging

Logging is the automatic recording of system or application events — it's like keeping a diary of what the system is doing.

Examples:

- Web server logs recording IPs and endpoints hit

- Application logs showing errors or user actions

- API request logs

📌 Goal: Enable debugging, monitoring, and behavioral analysis.

External Data

This refers to data sourced from outside your system, like 3rd-party APIs or public datasets.

Examples:

- Weather data from a public API

- Economic indicators from government datasets

- Industry benchmarks from data providers

📌 Goal: Enrich internal data with external context.

Clickstream Data

Clickstream data tracks how users navigate through a website or app, capturing sequences of events.

Examples:

- Page views

- Clicks, hovers, scrolls

- Session paths (e.g., Home → Product → Checkout)

📌 Goal: Understand user behavior and intent.

Sensors

Sensors collect physical world signals and convert them into data.

Examples:

- IoT temperature sensors in smart homes

- GPS sensors in phones or delivery vehicles

- Accelerometers in fitness trackers

📌 Goal: Capture real-time data from the physical environment.

User-Generated Content

This is any content that users make themselves, either actively or passively.

Examples:

- Product reviews or ratings

- Uploaded photos or videos

- Social media comments

📌 Goal: Leverage user input for insights, personalization, or community building.

Move / Store

The Move/Store stage of the Data Hierarchy of Needs is all about getting the data from its source to where it can be used — reliably, at scale, and efficiently.

Here's what each part means:

Reliable Data Flow

This ensures that data moves consistently and accurately from one system to another without loss, duplication, or delay.

Examples:

- Streaming events from Kafka to a data warehouse

- Replaying missed events without data corruption

- Acknowledging successful ingestion to prevent reprocessing

📌 Goal: Trust that your data is flowing smoothly and predictably.

Infrastructure

Infrastructure includes the compute, storage, and networking resources that support data movement and storage.

Examples:

- Cloud VMs or serverless compute (e.g., AWS Lambda, GCP Dataflow)

- Object storage systems like S3, and data warehouses like BigQuery

📌 Goal: Provide the foundation for scalable and secure data systems.

Pipelines

Pipelines are automated systems that move and transform data from source to destination in a defined sequence.

Examples:

- An ingestion pipeline that moves data from APIs to a database

- A transformation pipeline that cleans and joins datasets daily

- Real-time pipelines using tools like Kafka, Flink, or Spark

📌 Goal: Automate reliable and repeatable data movement and processing.

ETL (Extract, Transform, Load)

ETL refers to the process of extracting data, cleaning or transforming it, and loading it into a final system like a warehouse or database.

- Extract: Pull raw data from sources

- Transform: Clean, format, join, or enrich data

- Load: Store the final dataset where it can be queried or used

📌 Goal: Prepare data for consumption by analytics, ML, or applications.

Data Storage

This is where data lives long-term, structured in a way that it can be easily accessed, queried, or analyzed.

Examples:

- Cloud object storage: AWS S3, GCP Cloud Storage

- Data warehouses: Snowflake, BigQuery, Redshift

- Data lakes: Delta Lake, Apache Hudi

- Databases: PostgreSQL, MySQL, MongoDB

📌 Goal: Store data cost-effectively while ensuring durability and accessibility.

Explore / Transform

The Explore and Transform stage of the Data Hierarchy of Needs is where raw data is shaped into something useful for analysis or modeling. Here's a breakdown of the three components you mentioned:

Cleaning

This is about removing errors and inconsistencies from raw data to make it usable.

Examples:

- Handling missing values (e.g., filling, dropping, or imputing)

- Removing duplicates

- Fixing typos or inconsistent formatting (e.g., NY vs. New York)

- Normalizing units (e.g., converting kg to lbs)

- Removing out-of-range or nonsensical values (e.g., negative age)

📌 Goal: Make the data trustworthy and consistent.

Preparation

This involves transforming clean data into a form suited for analysis or modeling.

Examples:

- Feature engineering (e.g., creating a new column age from

birth_date) - Encoding categorical variables (e.g., one-hot encoding country)

- Aggregating data (e.g., average sales per region)

- Joining datasets

- Converting timestamps to time-based features (e.g., extracting hour, day)

📌 Goal: Reshape data to match your downstream tasks (analytics, ML, etc.).

Anomaly Detection

This is the process of identifying unexpected, unusual, or suspicious data points that could indicate errors or rare events.

Examples:

- Detecting sensor spikes or dropouts

- Finding sudden changes in user behavior

- Catching fraudulent transactions

- Identifying system malfunctions from log data

📌 Goal: Spot and address data quality issues or operational anomalies before they affect insights or models.

Aggregate / Label

The Aggregate & Label stage of the Data Hierarchy of Needs is about creating summarized, structured, and labeled data that supports analysis, ML, and business insights. Let’s break down each term:

Analytics

This is the process of examining data to draw insights, usually through queries, reports, and dashboards.

Examples:

- “What were last month’s top-selling products?”

- “How many users churned in Q4?”

- “Which regions saw a drop in revenue?”

📌 Goal: Support business decisions with summarized views of data.

Metrics

Metrics are quantifiable measurements used to track performance over time.

Examples:

- Conversion rate

- Monthly active users (MAU)

- Average order value (AOV)

- Customer retention rate

📌 Goal: Provide standardized KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) that align teams.

Segments

Segments are subsets of data grouped by shared characteristics.

Examples:

- Users who bought more than $500 in the last 30 days

- Customers from urban areas

- Sessions that lasted longer than 10 minutes

📌 Goal: Enable targeted analysis, personalization, or experimentation.

Aggregates

Aggregates are summarized data values computed from raw data, often using functions like sum(), avg(), count(), etc.

Examples:

- Total revenue per day

- Average time on site per user

- Number of purchases per product category

📌 Goal: Reduce data volume and highlight meaningful patterns.

Features

In machine learning, features are input variables used to train a model.

Examples:

- User’s average purchase frequency

- Total login count in the past 7 days

- Text embeddings from product descriptions

📌 Goal: Create informative variables that help ML models make predictions.

Training Data

This is labeled data used to train machine learning models.

Examples:

- Emails labeled as spam or not spam

- Product images labeled with categories

- Customer sessions labeled as conversion or no conversion

📌 Goal: Provide examples of correct behavior for supervised learning.

Learn / Optimize

The Learn/Optimize stage in the Data Hierarchy of Needs is the pinnacle — it's where data actually drives decisions or automation through learning, experimentation, and predictive models.

A/B Testing

A/B testing is a method of comparing two or more versions of something (like a web page or product feature) to see which performs better.

How it works: Split users into groups → Show each group a different version (A or B) → Measure outcomes (e.g., clicks, purchases).

Purpose: Understand which version leads to better results using data-driven evidence.

📌 Think of it as controlled experimentation to validate ideas.

Experimentation

A broader concept than A/B testing, experimentation includes testing changes or ideas under controlled conditions to learn causal effects.

Examples:

- Multivariate testing (testing more than two versions)

- Holdout groups for comparing against a baseline

- Business process changes (e.g., pricing, UI changes)

📌 Goal: Use experiments to explore how changes impact behavior or outcomes.

Classical Machine Learning (ML)

This includes well-established algorithms that learn patterns from data to make predictions or decisions.

Examples:

- Linear regression, decision trees, random forests, SVM's

- Used in fraud detection, churn prediction, demand forecasting

📌 Used when the data and problem are well-structured and interpretable.

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

AI is a broader field focused on building systems that can perform tasks that usually require human intelligence.

Examples:

- Chatbots, recommendation engines, voice assistants

- AI includes ML, but also covers symbolic systems, planning, and reasoning.

📌 Goal: Build intelligent systems that can perceive, reason, and act.

Deep Learning (DL)

Deep Learning is a subset of ML based on neural networks with many layers, designed to learn complex representations of data.

Examples:

- Image classification, speech recognition, natural language processing (e.g., ChatGPT)

- Technologies: TensorFlow, PyTorch

📌 Used when the problem is too complex for classical ML and massive data is available.

What's the focus for Data Engineer?

So, even though almost everyone is focused on AI/ML applications, a strong Data Engineering Team should provide them with a infrastructure that has:

- Instrumentation, Logging, Support a Variety of Data Sources.

- Reliable Data Flow, Cleaning.

- Monitoring & Useful Metrics.

These are really simple things, but they can be really hard to implement in complex systems. 🤭

As an engineer, we work under constraints. We must optimize along these axes:

- Cost - How much money it takes to build, run, and maintain something.

- Agility - How fast we can make changes, fix things, or try new ideas.

- Scalability - How well the system handles more work or more users without breaking.

- Simplicity - How easy it is to understand, use, and maintain the system.

- Reuse - How often we can use the same code, data, or design in different places.

- Interoperability - How easily things work together, even if they’re from different teams, systems, or tools.

Data Maturity

Another great idea from this chapter is Data Maturity.

Data Maturity refers to the organization's advancement in utilizing, integrating, and maximizing data capabilities.

Data maturity isn’t determined solely by a company’s age or revenue; an early-stage startup may demonstrate higher data maturity than a century-old corporation with billions in annual revenue.

What truly matters is how effectively the company leverages data as a competitive advantage.

Let's understand this with some examples:

🍼 Low Data Maturity

Example: A small retail store writes sales down in a notebook.

- Data is scattered or not digital.

- No real insights, just raw facts.

- Decisions are made by gut feeling or experience.

🧒 Early Data Maturity

Example: A startup uses Excel to track customer data and email open rates.

- Data is digital but siloed (spread across tools).

- Some basic analysis is done manually.

- Decisions use data occasionally, not consistently.

🧑🎓 Growing Data Maturity

Example: A mid-sized company uses a dashboard to track user behavior and marketing ROI.

- Data is centralized in a data warehouse.

- Teams access metrics through BI tools.

- Data helps make better business decisions.

🧠 High Data Maturity

Example: An e-commerce company uses real-time data to personalize recommendations and detect fraud.

- Data flows automatically across systems.

- Teams experiment and optimize based on data.

- Machine learning is part of everyday operations.

🧙 Very High Data Maturity

Example: A global tech company automatically retrains ML models, predicts demand, and adjusts supply chain in real-time.

- Data is a core strategic asset.

- All decisions are data-driven.

- Innovation, automation, and experimentation are the norm.

How to become a Data Engineer ? 🥳

Data engineering is a rapidly growing field, but lacks a formal training path. Universities don't offer standardized programs, and while boot camps exist, a unified curriculum is missing.

People enter the field with diverse backgrounds, often transitioning from roles like software engineering or data analysis, and self-study is crucial. 🏂

A data engineer must master data management, technology tools, and understand the needs of data consumers like analysts and scientists.

Success in data engineering requires both technical expertise and a broader understanding of the business impact of data.

Business Responsibilities:

- Know how to communicate with nontechnical and technical people.

Example: You’re building a dashboard for the marketing team. You explain in simple terms how long it will take and ask them what insights matter most—without using technical jargon like “ETL pipelines” or “schema evolution.” Then you talk to your fellow engineers in detail about data modeling and infrastructure.

- Understand how to scope and gather business and product requirements.

Example: A product manager says, “We want to know why users drop off after sign-up.” You don’t just jump into building something—you ask follow-up questions: “What’s your definition of drop-off? Are we looking at mobile or web users? Over what time frame?”

- Understand the cultural foundations of Agile, DevOps, and DataOps.

Example: You don’t wait months to launch a data product. Instead, you release a small working version (MVP), get feedback from stakeholders, and iterate quickly. You write tests and automate your pipeline deployments using CI/CD like a software engineer.

- Control costs.

Example: Instead of running an expensive BigQuery job every hour, you optimize the SQL and reduce the schedule to once every 6 hours—saving the company hundreds or thousands of dollars a month in compute costs.

- Learn continuously.

Example: You hear your team wants to adopt Apache Iceberg. You’ve never used it, so you take an online course, read the docs, and build a mini project over the weekend to see how it works.

A successful data engineer always zooms out to understand the big picture and how to achieve outsized value for the business.

Technical Responsibilities:

Data engineers remain software engineers, in addition to their many other roles.

What languages should a data engineer know?

- SQL: lingua franca of data

- Python: Bridge between Data Engineering and Data Science.

- JVM languages such as Java and Scala: Crucial for open source data frameworks.

- bash: cli of Linux OS. Which is the leading operating system on servers (over 96.4% of the top one million web servers' operating systems are Linux.).

You can also add a CI/CD tool like Jenkins, containerization with Docker, and orchestration with Kubernetes to this list.

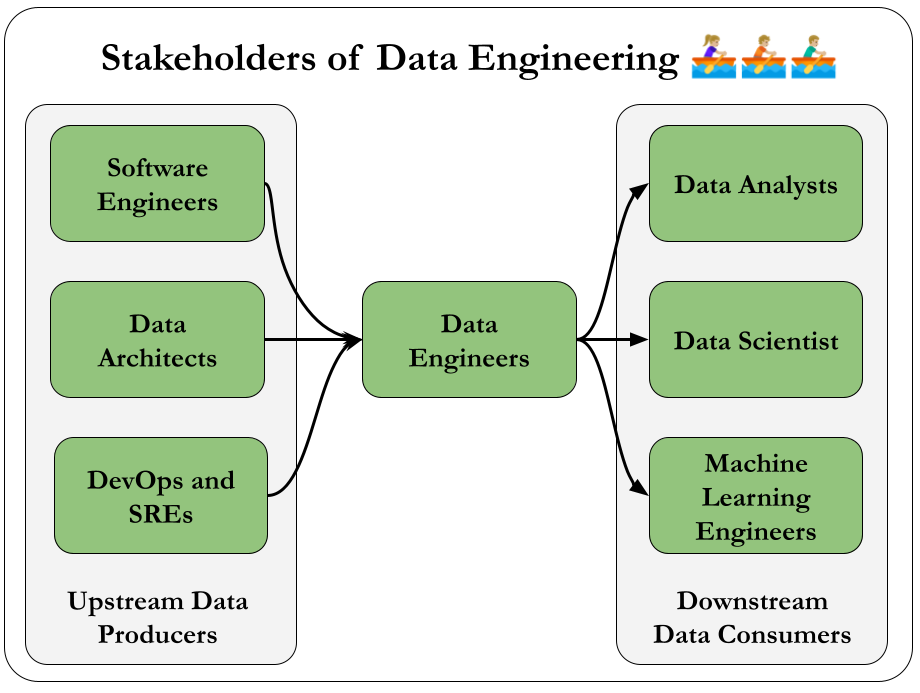

Data Engineers and Other Technical Roles

It is important to understand the technical stakeholders that you'll be working with.

The crucial idea is that, you are a part of a bigger team. As a unit, you are trying to achieve something. 🏉

A great tactic would be to understand the workflows of those people which sits at the upstream or downstream of your work.

So feel free to research all technical roles with a prompt to an LLM like following:

As a Data Engineer a stakeholder of mine are Machine Learning Engineers. Can you help me understand what they do, how they do it and how's their work quality measured? I want to serve them in the best way possible.

Data Engineers and Leadership

Data engineers act as connectors within organizations, bridging business and data teams.

They now play a key role in strategic planning, helping align business goals with data initiatives and supporting data architects in driving data-centric projects.

Data in the C-Suite

C-level executives increasingly recognize data as a core asset.

The CEO typically partners with technical leaders on high-level data strategies without diving into technical specifics.

The CIO focuses on internal IT systems and often collaborates with data engineers on initiatives like cloud migrations and infrastructure planning.

The CTO handles external-facing technologies, working with data teams to integrate information from customer-facing platforms such as web and mobile applications.

The Chief Data Officer (CDO) oversees data strategy and governance, ensuring data delivers tangible business value.

There are other examples, but these are enough to demonstrate the value we bring as data engineers.

Conclusion

Now we know about:

- What is a Data Engineer and what does s/he do

- The Lifecycle they use

- The people they work with

Let's dive deep on the lifecycle. 🥳

2. The Data Engineering Lifecycle. 🐦

We can move beyond viewing data engineering as a specific collection of data technologies, which is a big trap. 😮

We can think with data engineering lifecycle. 💯

It shows the stages that turn raw data ingredients into a useful end product, ready for consumption by analysts, data scientists, ML engineers, and others.

Let's remember the figure for the lifecycle.

In the following chapters we'll dive deep for each of these stages, but let's learn the useful questions to ask about them first.

Arguably, the most impactful contribution we can make lies in the answers to these questions. Regardless of the company structure or the system we’re working on, asking the right questions about data generation, ingestion, storage, transformation, and serving allows us to identify opportunities for improvement and drive meaningful change.

Generation: Source Systems 🌊

A source system is where data originates in the data engineering process.

Examples of source systems include IoT devices, application message queues, or transactional databases.

Data engineers use data from these source systems but typically do not own or control them.

Therefore, it's important for data engineers to understand how these source systems operate, how they generate data, how frequently and quickly they produce data (frequency & velocity) and the different types of data they generate.

Here is a set of evaluation questions for Source Systems:

- What are the essential characteristics of the data source? Is it an application? A swarm of IoT devices?

- How is data persisted in the source system? Is data persisted long term, or is it temporary and quickly deleted?

- At what rate is data generated? How many events per second? How many gigabytes per hour?

- What level of consistency can data engineers expect from the output data? If you’re running data-quality checks against the output data, how often do data inconsistencies occur—nulls where they aren’t expected, lousy formatting, etc.?

- How often do errors occur?

- Will the data contain duplicates?

- Will some data values arrive late, possibly much later than other messages produced simultaneously?

- What is the schema of the ingested data? Does a join across several tables or even several systems needed to get a complete picture of the data?

- If schema changes (say, a new column is added), how is this dealt with and communicated to downstream stakeholders?

- How frequently should data be pulled from the source system? Will Ingestion be a thread for source system in terms of resource contention?

- For stateful systems (e.g., a database tracking customer account information), is data provided as periodic snapshots or update events from change data capture (CDC)? What’s the logic for how changes are performed, and how are these tracked in the source database?

- Who/what is the data provider that will transmit the data for downstream consumption?

- Will reading from a data source impact its performance?

- Does the source system have upstream data dependencies? What are the characteristics of these upstream systems?

- Are data-quality checks in place to check for late or missing data?

We'll learn more about Source Systems in Chapter 5.

Storage 🌱

Choosing the right data storage solution is critical yet complex in data engineering because it affects all stages of the data lifecycle.

Cloud architectures often use multiple storage systems that offer capabilities beyond storage, like data transformation and querying.

Storage intersects with other stages such as ingestion, transformation, and serving, influencing how data is used throughout the entire pipeline.

Here is a set of evaluation questions for Storage:

- Is the storage solution compatible with the architecture’s required read and write speeds to prevent bottlenecks in downstream processes?

- Are we utilizing the storage technology optimally without causing performance issues (e.g., avoiding high rates of random access in object storage systems)?

- Can the storage system handle anticipated future scale in terms of capacity limits, read/write operation rates, and data volume?

- Will downstream users and processes be able to retrieve data within the required service-level agreements (SLAs - more on this later) ?

- Are we capturing metadata about schema evolution, data flows, and data lineage to enhance data utility and support future projects?

- Is this a pure storage solution, or does it also support complex query patterns (like a cloud data warehouse) ?

- Does the storage system support schema-agnostic (object storage) storage, flexible schemas (Cassandra), or enforced schemas (DWH) ?

- How are we tracking master data, golden records, data quality, and data lineage for data governance?

- How are we handling regulatory compliance and data sovereignty, such as restrictions on storing data in certain geographical locations?

Regardless of the storage type, the temperature of data is a good frame to interpret storage and data.

Data access frequency defines data "temperatures": Hot data is frequently accessed and needs fast retrieval; lukewarm data is accessed occasionally; cold data is rarely accessed and suited for archival storage. Cloud storage tiers match these temperatures, balancing cost with retrieval speed.

We'll learn more about Storage in Chapter 6.

Ingestion 🧘♂️

Data ingestion from source systems is a critical stage in the data engineering lifecycle and often represents the biggest bottleneck.

Source systems are typically outside of our control and may become unresponsive or provide poor-quality data.

Ingestion services might also fail for various reasons, halting data flow and impacting storage, processing, and serving stages. These unreliabilities can ripple across the entire lifecycle, but if we've addressed the key questions about source systems, we can better mitigate these challenges.

Here is a set of evaluation questions for Ingestion:

- What are the purposes of the data we are ingesting? Can we utilize this data without creating multiple versions of the same dataset?

- Do the systems that generate and ingest this data operate reliably, and is the data accessible when needed?

- After ingestion, where will the data be stored or directed?

- How often will we need to access or retrieve the data?

- What is the typical volume or size of the data that will be arriving?

- In what format is the data provided, and can the downstream storage and transformation systems handle this format?

- Is the source data ready for immediate use downstream? If so, for how long will this be the case, and what could potentially make it unusable?

Batch processing is often preferred over streaming due to added complexities and costs; real-time streaming should be used only when necessary.

Data ingestion involves push models (source sends data) and pull models (system retrieves data), often combined in pipelines. Traditional ETL uses the pull model.

Continuous Change Data Capture (CDC) can be push-based (triggers on data changes) or pull-based (reading logs).

Streaming ingestion pushes data directly to endpoints, ideal for scenarios like IoT sensors emitting events, simplifying real-time processing by treating each data point as an event.

We'll learn more about Ingestion in Chapter 7.

Transformation 🔨

After data is ingested and stored, it must be transformed into usable formats for downstream purposes like reporting, analysis, or machine learning.

Transformation converts raw, inert data into valuable information by correcting data types, standardizing formats, removing invalid records, and preparing data for further processing.

This preparation can be applying normalization, performing large-scale aggregations for reports or extracting features for ML models.

Here is a set of evaluation questions for Transformation:

- What are the business requirements and use cases for the transformed data?

- What data quality issues exist, and how will they be addressed?

- What transformations are necessary to make the data usable?

- What are the source data formats, and what formats are required by downstream systems?

- Are there schema changes needed during transformation?

- How will we handle varying data types and ensure correct type casting?

- What is the expected data volume, and how will it affect processing performance?

- Which tools and technologies are best suited for the transformation tasks?

- How will we manage and track data lineage (history and life cycle of data as it moves through in the data pipeline) and provenance ?

- What are the performance requirements and SLAs for the transformation process?

- Are there regulatory compliance or security considerations?

- How can we validate and test the transformed data for accuracy and completeness?

- What error handling and logging mechanisms will be in place?

- Is real-time or batch processing required?

- How can we handle changes in source data schemas or structures over time?

- How will the transformed data be stored and accessed downstream?

- What documentation is needed for the transformation logic and pipeline architecture?

- How should we you monitor and maintain the transformation pipeline over time?

- What are the data governance policies that need to be enforced during transformation?

- How can we ensure scalability of the transformation process as data volumes grow?

- Are there any data enrichment (integrating additional data sources to enhance the value of the transformed data) opportunities during transformation?

- How can we secure data during transformation to prevent unauthorized access?

Transformation often overlaps with other stages of the data lifecycle, such as ingestion, where data may be enriched or formatted on the fly.

Business logic plays a significant role in shaping transformations, especially in data modeling, to provide clear insights into business processes and ensure consistent implementation across systems.

Additionally, data featurization is an important transformation for machine learning, involving the extraction and enhancement of data features for model training—a process that data engineers can automate once defined by data scientists.

We'll learn more about Transformation in Chapter 8.

Serving Data 🤹

After data is ingested, stored, and transformed, the goal is to derive value from it.

In the beginning of the book, we've seen how data engineering is enabling predictive analysis, descriptive analytics, and reports.

With simple terms, here is what they are:

- Predictive Analysis: Uses historical data and statistical models to forecast future events or trends.

- Descriptive Analytics: Examines past data to understand and summarize what has already occurred.

- Reports: Compile and present data and insights in a structured format for informed decision-making.

Here is a set of questions to make a solid Serving Stage:

- What are the primary business goals we aim to achieve with this data?

- Who are the key stakeholders, and how will they use the data?

- Which specific use cases will the data serving support (e.g., reporting, machine learning, real-time analytics)?

- How does the data align with our overall business strategy and priorities?

- What data validation and cleansing processes are in place to maintain quality?

- How do we handle data inconsistencies or errors in the serving stage?

- Who needs access to the data, and what are their access levels?

- What access controls and permissions are required to secure the data?

- What reporting tools and dashboards will be used to visualize the data?

- How can we enable self-service analytics for business users without compromising data security?

- What key performance indicators (KPIs) and metrics should be tracked?

- Do we need to implement a feature store to manage and serve features for ML?

- How will we handle feature versioning and sharing across teams?

- What security measures are in place to protect sensitive and confidential data?

- How do we ensure compliance with data privacy regulations (e.g., GDPR, CCPA)?

- What encryption methods are used for data at rest and in transit?

- What latency requirements do we have for data access and real-time analytics?

- Are there performance monitoring tools in place to track and optimize data serving?

- How are responsibilities divided between data engineering, ML engineering, and analytics teams?

ML is cool, but it’s generally best to develop competence in analytics before moving to ML.

We'll dive deep on Serving in Chapter 9.

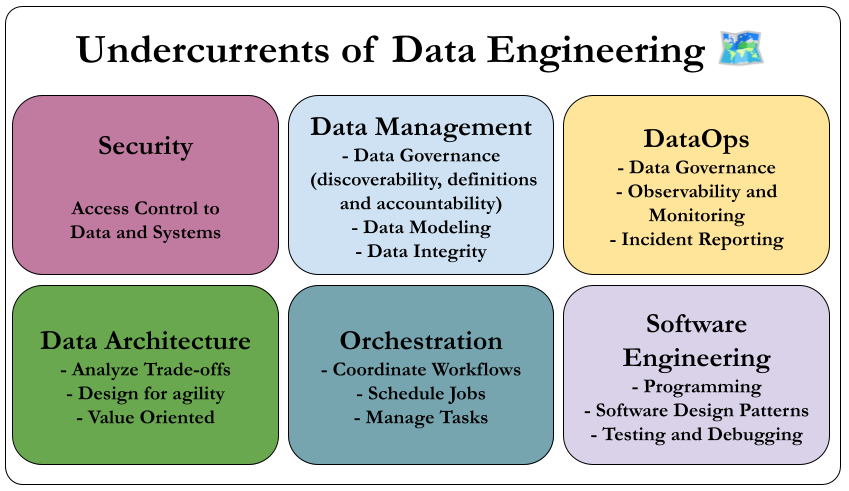

The Undercurrents

Data engineering is evolving beyond just technology, integrating traditional practices like data management and cost optimization with newer approaches such as DataOps.

These key "undercurrents"—including security, data architecture, orchestration, and software engineering—support the entire data engineering lifecycle.

Let's talk about them in single sentences, and we'll go into explore them in greater detail throughout the book.

Security

Security is paramount in data engineering, requiring engineers to enforce the principle of least privilege, cultivate a security-focused culture, implement robust access controls and encryption, and possess comprehensive security administration skills to effectively protect sensitive data.

Data Management

Modern data engineering integrates comprehensive data management practices—such as governance and lifecycle management—transforming it from a purely technical role into a strategic function essential for treating data as a vital organizational asset.

DataOps

DataOps applies Agile and DevOps principles to data engineering by fostering a collaborative culture and implementing automation, monitoring, and incident response practices to enhance the quality, speed, and reliability of data products.

Data Architecture

Data architecture is a fundamental aspect of data engineering that involves understanding business requirements, designing cost-effective and simple data systems, and collaborating with data architects to support an organization’s evolving data strategy.

Orchestration

Orchestration in DataOps is the coordinated management of data jobs using systems like Apache Airflow to handle dependencies, scheduling, monitoring, and automation, ensuring efficient and reliable execution of data workflows.

Software Engineering

Software engineering is fundamental to data engineering, encompassing the development and testing of data processing code, leveraging and contributing to open source frameworks, managing streaming complexities, implementing infrastructure and pipelines as code, and addressing diverse technical challenges to support and advance evolving data systems.

Conclusion 🌠

The data engineering lifecycle, supported by key undercurrents such as security, data management, DataOps, architecture, orchestration, and software engineering, provides a comprehensive framework for data engineers to optimize ROI, reduce costs and risks, and maximize the value and utility of data.

Let's learn to think with this mindset! 🧠

3. Designing Good Data Architecture 🎋

What is it? Here is a definition:

- Data architecture is the design of systems to support the evolving data needs of an enterprise, achieved by flexible and reversible decisions reached through a careful evaluation of trade-offs.

We can divide Data Architecture into two parts, Operational and Technical.

Here are my definitions:

Operational architecture involves the practical needs related to people, processes, and technology. For example, it looks at which business activities the data supports, how the company maintains data quality, and how quickly data needs to be available for use after it's made.

Technical architecture explains the methods for collecting, storing, changing, and delivering data throughout its lifecycle. For example, it might describe how to move 10 TB of data every hour from a source database to a data lake.

In short, operational architecture defines what needs to be done, while technical architecture explains how to do it.

Effective data architecture meets business needs by using standardized, reusable components while remaining adaptable and balancing necessary compromises. It's also dynamic and continually evolving. It is never truly complete.

By definition, adaptability and growth are fundamental to the essence and objectives of data architecture.

Next, let's explore the principles that underpin good data architecture. 😌

Principles of Good Data Architecture ✅

Here are 9 principles to keep in mind.

1: Choose Common Components Wisely

A key responsibility of data engineers is selecting shared components and practices—such as object storage, version control systems, observability tools, orchestration platforms, and processing engines—that are widely usable across the organization.

Effective selection promotes collaboration, breaks down silos, and enhances flexibility by leveraging common knowledge and skills.

These shared tools should be accessible to all relevant teams, encouraging the use of existing solutions over creating new ones, while ensuring robust permissions and security to safely share resources.

Cloud platforms are ideal for implementing these components, allowing teams to access a common storage layer with specialized tools for their specific needs.

Balancing organizational-wide requirements with the flexibility for specialized tasks is essential to support various projects and foster collaboration without imposing one-size-fits-all solutions.

Further details are provided in Chapter 4.

2: Plan for Failure

Modern hardware is generally reliable, but failures are inevitable over time.

To build robust data systems, it's essential to design with potential failures in mind by understanding key concepts such as availability (the percentage of time a service is operational), reliability (the likelihood a system performs its intended function), recovery time objective (the maximum acceptable downtime), and recovery point objective (the maximum acceptable data loss).

These factors guide engineers in making informed architectural decisions to effectively handle and mitigate failure scenarios, ensuring systems remain resilient and meet business requirements.

3: Architect for Scalability

Scalability in data systems means the ability to automatically increase capacity to handle large data volumes or temporary spikes and decrease it to reduce costs when demand drops.

Elastic systems adjust dynamically, sometimes even scaling to zero when not needed, as seen in serverless architectures. However, choosing the right scaling strategy is essential to avoid complexity and high costs.

This requires carefully assessing current usage, anticipating future growth, and selecting appropriate database architectures to ensure efficiency and cost-effectiveness as the organization expands.

4: Architecture Is Leadership

Data architects combine strong technical expertise with leadership and mentorship to make technology decisions, promote flexibility and innovation, and guide data engineers in achieving organizational goals.

It really helps to have a growth mindset. 🧠

5: Always Be Architecting ♻️

Data architects continuously design and adapt architectures in an agile, collaborative way, responding to business and technology changes by planning and prioritizing updates.

Innovation requires iteration. Mark Papermaster.

6: Build Loosely Coupled Systems

Loose coupling through independent components and APIs allows teams to collaborate efficiently and evolve systems flexibly.

7: Make Reversible Decisions

To stay agile in a rapidly changing data landscape, architects should make reversible decisions that keep architectures simple and adaptable.

You can read this shareholder letter from Jeff Bezos on reversible decisions.

8: Prioritize Security

Data engineers must take responsibility for system security by adopting zero-trust models and the shared responsibility approach, ensuring robust protection in cloud-native environments and preventing breaches through proper configuration and proactive security practices.

9: Embrace FinOps

FinOps is a cloud financial management practice that encourages collaboration between engineering and finance teams to optimize cloud spending through data-driven decisions and continuous cost monitoring.

We should embrace FinOps! It helps us defend our decisions.

Now that we have a grasp of the fundamental principles of effective data architecture, let's explore the key concepts necessary for designing and building robust data systems in more detail.

Major Architecture Concepts

To learn more about:

- Domains and Services

- Distributed Systems, Scalability, and Designing for Failure

- Tight Versus Loose Coupling: Tiers, Monoliths, and Microservices

- User Access: Single Versus Multitenant

- Event-Driven Architecture

- Brownfield Versus Greenfield Projects

please read this part. 🥰

Next, we’ll explore different types of architectures.

Examples and Types of Data Architecture

Here, we can explore some 101 information about:

-

Data Warehouse – Centralized, structured, query-optimized storage.

-

Data Marts – Department-specific subsets of warehouse data.

-

Data Lake – Raw, unstructured data stored at scale.

-

Data Lakehouses – Data lake + warehouse features combined.

-

The Modern Data Stack – Cloud-native, modular data tooling ecosystem.

-

Lambda Architecture – Combines batch and real-time processing.

-

Kappa Architecture – Streaming-only alternative to Lambda.

-

Unified Batch and Streaming – One engine for all data flows.

-

IoT Architecture – Real-time pipelines for connected devices.

-

Data Mesh – Decentralized, domain-owned data architecture.

which is foundational knowledge on which what we'll build after.

Conclusion

Architectural design involves close collaboration with business teams to weigh different options.

For instance:

-

How does choosing a cloud data warehouse compare to implementing a data lake?

-

What considerations come into play when selecting between cloud providers?

-

Under what circumstances would a unified processing system like Flink or Beam make sense?

Gaining a strong grasp of these decision points will equip us to make sound, reasonable choices.

Next, we’ll explore approaches to selecting the right technologies for our data architecture and throughout the data engineering lifecycle. 😍

4. Choosing Technologies Across the Data Engineering Lifecycle

Chapter 3 explored the concept of good data architecture and its importance.

Now, we shift focus to selecting the right technologies to support this architecture.

For data engineers, choosing the right tools is crucial for building high-quality data products.

The key question to ask when evaluating a technology is straightforward:

Does it add value to the data product and the broader business? 💡

One common misconception is equating architecture with tools.

Architecture is strategic, while tools are tactical.

-

Architecture is the high-level design, roadmap, and blueprint that guides how data systems align with strategic business objectives. It answers the what, why, and when of data systems.

-

Tools, on the other hand, are the how—the practical means of implementing the architecture.

Key Factors for Choosing Data Technologies

When selecting technologies to support your data architecture, consider the following across the data engineering lifecycle:

-

Team Size and Capabilities: Can your team effectively manage and scale the technology? 👥

-

Speed to Market: Does it help deliver results quickly? 🚀

-

Interoperability: How well does it integrate with existing systems? 🔗

-

Cost Optimization and Business Value: Is the cost justified by the value it provides? 💰

-

Today vs. Future: Is the technology immutable (long-term) or transitory (short-term)? 📅

-

Deployment Location: Cloud, on-premises, hybrid, or multicloud—what fits best? ☁️🏢

-

Build vs. Buy: Should you make a custom solution or use an off-the-shelf tool? What about open source software? 🛠️🛒

-

Monolith vs. Modular: Is a single unified system better, or should it be broken into smaller, interchangeable parts? 🧱

-

Serverless vs. Servers: Which offers better scalability and cost efficiency for your use case? ⚙️

-

Optimization and Performance: How does the technology perform, and how does it compare in benchmarks? 🏎️

-

The Undercurrents of the Data Engineering Lifecycle: Consider hidden complexities and future challenges. 🌊

These points might be helpful for you to demonstrate that your approach is rooted in industry best practices and aligned with the system’s goals.

Read this part in detail on how to choose the right tooling.

Continue with the second part of the book here 🥳

Part 2 – The Data Engineering Lifecycle in Depth 🔬

Then we move onto the second part of the book, which helps us understand the core idea.

5. Data Generation in Source Systems

Before getting the raw data, we must understand where the data exists, how it is generated, and its characteristics.

Let's make sure we get the absolute basics about source systems correctly. 🍓

Main Ideas on Source Systems

Files

A file is a sequence of bytes, typically stored on a disk. Applications often write data to files. Files may store local parameters, events, logs, images, and audio.

In addition, files are a universal medium of data exchange. As much as data engineers wish that they could get data programmatically, much of the world still sends and receives files.

APIs

API's are a standard data exchange method.

A simple example would be the "log in with Twitter/Google/GitHub" capability seen on many websites. Rather than entering into users' social media accounts (which would be a severe security risk), applications with this capability use the APIs of these platforms to authenticate the user with each login.

Application Databases (OLTP)

Application databases store app state with fast, high-volume reads/writes.

They are ideal for transactional tasks like banking. Commonly low-latency, high-concurrency systems—RDBMS, document, or graph DBs.

More info about ACID and atomic transactions can be found here.

OLAP Systems

Built for large, interactive analytics—relatively slower at single-record lookups. Often used in ML pipelines or reverse ETL.

Change Data Capture (CDC)

CDC, captures DB changes (insert/update/delete) for real-time sync or streaming. Implementation varies by database type.

Database Logs store operations before execution for recovery. Key for CDC and reliable event streams.

Logs

Logs are tracked system events for analysis or ML. Common sources: OS, apps, servers, networks. Formats: binary, semi-structured (e.g. JSON), or plain text.

Log Resolution defines how much detail logs capture. Log level controls what gets recorded (e.g., errors only). Logs can be batch or real-time.

CRUD

Create, Read, Update, Delete.

Core data operations in apps and databases. Common in APIs and storage systems.

Insert-Only

Instead of updates, new records are inserted with timestamps. This is great for history, but tables grow fast and lookups get costly.

Messages and Streams

Messages are single-use signals between systems. Once the message is received, and the action is taken, the message is removed from the message queue.

Streams are ordered, persistent logs of events for long-term processing. With append only nature, records in a stream are persisted over a retention window.

Streaming platforms often handle both.

Types of Time

- Event Time: When the event happened.

- Ingestion Time: When it entered your system.

- Processing Time: When it was transformed.

Track all to monitor delays and flow.

Source Systems Practical Details

Here are some practical knowledge of APIs, databases, and data flow tools is essential but ever-changing—stay current.

Relational Databases (RDBMS)

Structured, ACID-compliant, great for transactional systems. They have tables, foreign keys, normalization, etc.

Examples would be PostgreSQL, MySQL, SQL Server, Oracle DB etc.

NoSQL Databases

Flexible, horizontally scalable databases with different data models.

Key-Value Stores

Fast read/write using unique keys. Great for caching or real-time event storage.

Examples would be Redis, Amazon DynamoDB etc.

Document Stores

Schema-flexible, store nested JSON-like documents.

Some examples are MongoDB, Couchbase, Firebase Firestore etc.

Wide-Column Stores

High-throughput databases that scale horizontally. They use column families and rows.

Some examples are Cassandra, ScyllaDB, Google Bigtable.

Graph Databases

Store nodes and edges. Ideal for analyzing relationships.

Examples could be given as Neo4j, Amazon Neptune, ArangoDB etc.

Search Databases

Fast search and text analysis engines. Common in logs and e-commerce.

Popular examples are Elasticsearch, Apache Solr, Algolia.

Time-Series Databases

Optimized for time-stamped data: metrics, sensors, logs.

Some examples would be InfluxDB, TimescaleDB, Apache Druid etc.

APIs

Standard for data exchange across systems, especially over HTTP.

REST (Representational State Transfer)

Stateless API style using HTTP verbs (GET, POST, etc.). Widely adopted but loosely defined—developer experience varies.

An example would be the GitHub REST API.

GraphQL

Made by Meta. Lets clients request exactly the data they need in one query—more flexible than REST.

Here is a link for the curious: GitHub GraphQL API.

Webhooks

Event-based callbacks from source systems to endpoints. Called reverse APIs because the server pushes data to the client.

Stripe Webhooks and Slack Webhooks are great examples.

RPC / gRPC

Run remote functions as if local. gRPC (by Google) uses Protocol Buffers and HTTP/2 for fast, efficient communication.

Check out gRPC by Google for more.

And More

There are more details about Data Sharing, Third-Party Data Sources, Message Queues and Event-Streaming Platforms.

Summary

Now we have a baseline for understanding source systems. The details matter.

We should work closely with app teams to improve data quality, anticipate changes, and build better data products. Collaboration leads to shared success—especially with trends like reverse ETL and event-driven architectures.

Making source teams part of the data journey is also a great idea.

Next: storing the data.

One additional note: Ideally our systems should be idempotent. An idempotent system produces the same result whether a message is processed once or multiple times—crucial for handling retries safely.

6. Storage 📦

Storage is core to every stage—data is stored repeatedly across ingestion, transformation, and serving.

Two things to consider while deciding on storage are:

- Use case of the data.

- The way you will retrieve it.

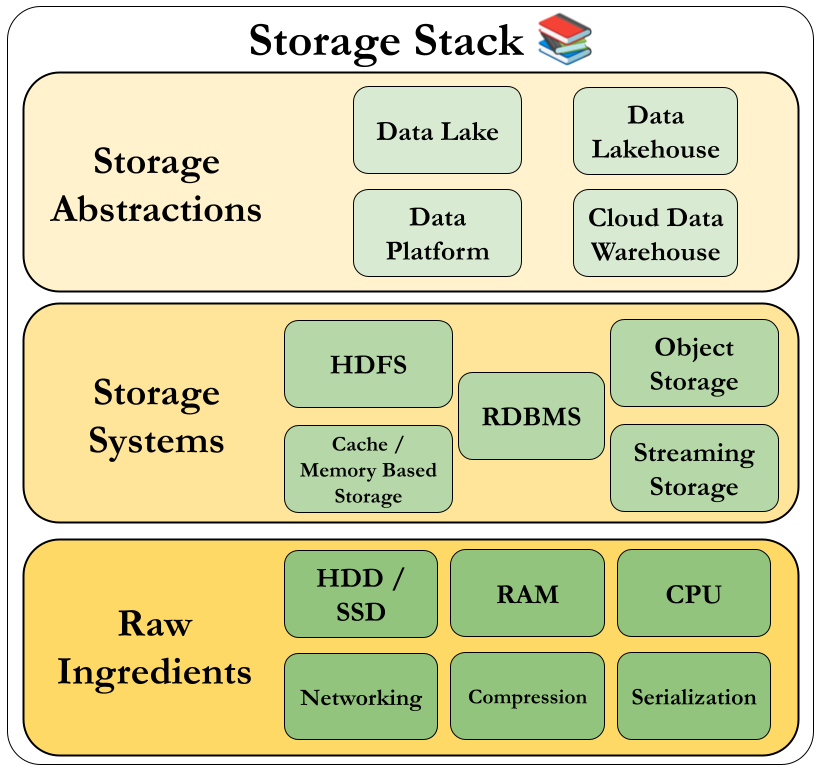

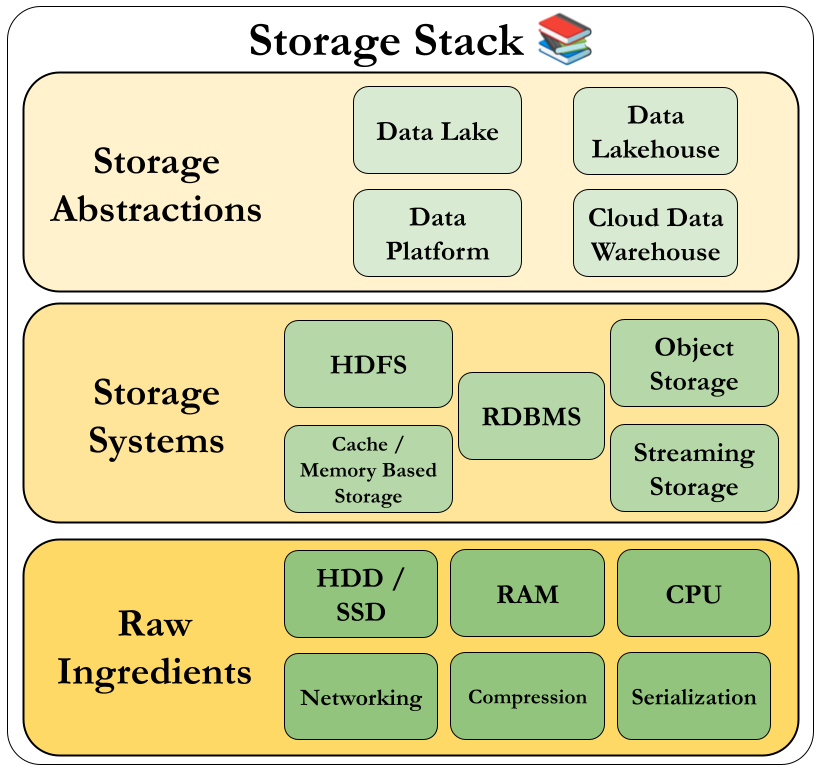

The way storage is explained in the book is with the following figure:

Raw Ingredients of Data Storage

Here are some one liners as definitions.

-

Magnetic Disk Drive – Traditional, cost-effective storage with moving parts; slower read/write.

-

Solid-State Drive (SSD) – Faster, durable storage with no moving parts.

-

Random Access Memory (RAM) – Temporary, ultra-fast memory used during active processing.

-

Networking and CPU – Key hardware for moving and processing data efficiently.

-

Serialization – Converts data into storable/transmittable formats.

-

Compression – Reduces data size for faster storage and transfer.

-

Caching – Stores frequently accessed data for quick retrieval.

Data Storage Systems

Operate above raw hardware—like disks—using platforms such as cloud object stores or HDFS. Higher abstractions include data lakes and lakehouses.

Here are some one liners about them.

-

Single Machine vs. Distributed Storage – Single-node is simple; distributed scales across machines for reliability and size.

-

Eventual vs. Strong Consistency – Eventual allows delay in syncing; strong guarantees immediate consistency.

-

File Storage – Stores data as files in directories; easy to use, widely supported.

-

Block Storage – Breaks data into blocks for fast, low-level access; used in databases and VMs.

-

Object Storage – Stores data as objects with metadata; ideal for large-scale, unstructured data.

-

Cache and Memory-Based Storage Systems – Keep hot data in fast memory for quick access.

-

The Hadoop Distributed File System (HDFS) – Distributed storage system for big data, fault-tolerant and scalable.

-

Streaming Storage – Handles continuous data flows; used for real-time analytics and pipelines.

-

Indexes, Partitioning, and Clustering – Techniques to speed up queries and organize large datasets.

Data Engineering Storage Abstractions

These are the abstractions that are built on top of storage systems.

Let's remember our map for storage.

Here are some of the Storage Abstractions.

-

The Data Warehouse – Data warehouses are a common OLAP architecture used to centralize analytics data. Once built on traditional databases, modern warehouses now rely on scalable cloud platforms like Google's BigQuery. It's a structured, query-optimized for analytics and BI workloads.

-

The Data Lake – Stores raw, unstructured data at scale for flexibility. Funnily enough, someone referred to a Data Lake as just files on S3.

-

The Data Lakehouse – Combines warehouse performance with lake flexibility in one system. This means incremental updates and deletes on schema managed tables.

-

Data Platforms – Unified environments managing storage, compute, and processing tools. Vendors are using this term as a singular place to solve problems.

-

Stream-to-Batch Storage Architecture – Buffers real-time data for batch-style processing later. Just like Lambda architecture, streaming data is sent to multiple consumers—some process it in real time for stats, while others store it for batch queries and long-term retention.

Big Ideas in Data Storage

Here are some big ideas in Storage.

🔍 Data Catalogs

Data catalogs are centralized metadata hubs that let users search, explore, and describe datasets.

They support:

-

Automated metadata scanning

-

Human-friendly interfaces

-

Integration with pipelines and data platforms

🔗 Data Sharing

Cloud platforms enable secure sharing of data across teams or organizations.

⚠️ This requires strong access controls to avoid accidental exposure.

🧱 Schema Management

Understanding structure is essential:

-

Schema-on-write: Enforces structure at ingestion; reliable and consistent.

-

Schema-on-read: Parses structure during query; flexible but fragile.

💡 Use formats like Parquet for built-in schema support. Avoid raw CSV.

⚙️ Separation of Compute & Storage

Modern systems decouple compute from storage for better scalability and cost control.

- Compute is ephemeral (runs only when needed).

- Object storage ensures durability and availability.

- Hybrid setups combine performance + flexibility.

🔁 Hybrid Storage Examples

- Amazon EMR: Uses HDFS + S3 for speed and durability.

- Apache Spark: Combines memory and local disk when needed.

- Apache Druid: SSD for speed, object storage for backup.

- BigQuery: Optimizes access via hybrid object storage.

📎 Zero-Copy Cloning

Clone data without duplicating it (e.g., Snowflake, BigQuery).

⚠️ Deleting original files may affect clones — know the limits.

📈 Data Storage Lifecycle & Retention

We talked about the temperature of data. Let's see an example.

🔥 Hot, 🟠 Warm, 🧊 Cold Data

| Type | Frequency | Storage | Cost | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot | Frequent | RAM/SSD | High | Recommendations, live queries |

| Warm | Occasional | S3 IA | Medium | Monthly reports, staging data |

| Cold | Rare/Archive | Glacier | Low | Compliance, backups |

Use lifecycle policies to move data between tiers automatically.

⏳ Retention Strategy

- Keep only what's valuable.

- Set Time-to-Live (TTL) on cache or memory.

- Consider regulatory needs (e.g., HIPAA, GDPR).

- Use cost-aware deletion or archival rules.

🏢 Single-Tenant vs Multitenant Storage

Single-Tenant

- Each tenant/customer has isolated resources and databases.

- Pros: Better privacy, schema flexibility.

- Cons: Harder to manage at scale.

Multitenant

- Tenants share the same database or tables.

- Pros: More efficient resource usage.

- Cons: Requires careful access control and query design.

Summary 😌

Storage is the backbone of the data engineering lifecycle—powering ingestion, transformation, and serving. As data flows through systems, it's stored multiple times across various layers, so understanding how, where, and why we store data is critical.

Smart storage decisions—paired with good schema design, lifecycle management, and collaboration—can drastically improve scalability, performance, and cost-efficiency in any data platform.

Here are 3 strong quotes from the book.

As always, exercise the principle of least privilege. Don’t give full database access to anyone unless required.

Data engineers must monitor storage in a variety of ways. This includes monitoring infrastructure storage components, object storage and other “serverless” systems.

Orchestration is highly entangled with storage. Storage allows data to flow through pipelines, and orchestration is the pump.

7. Ingestion

Ingestion is the process of moving data from source systems into storage—it's the first step in the data engineering lifecycle after data is generated.

Quick definition, data ingestion is data movement from point A to B, data integration combines data from disparate sources into a new dataset. Example of data integration is a CRM system, advertising analytics data, and web analytics to make a user profile, which is saved to our data warehouse.

A data pipeline is the full system that moves data through the data engineering lifecycle. Design of data pipelines typically starts at the ingestion stage.

What to Consider when Building Ingestion? 🤔

Consider these factors when designing your ingestion architecture:

Bounded vs. Unbounded

All data is unbounded until constrained. Streaming preserves natural flow; batching adds structure.

Frequency

Choose between batch, micro-batch, or real-time ingestion. "Real-time" typically means low-latency, near real-time.

Synchronous vs. Asynchronous

- Synchronous: Tightly coupled; failure in one stage stops all.

- Asynchronous: Loosely coupled; stages operate independently and more resiliently.

Serialization & Deserialization

Data must be encoded before transfer and properly decoded at destination. Incompatible formats make data unusable.

Throughput & Scalability

Design to handle spikes and backlogs. Use buffering and managed services (e.g., Kafka, Kinesis) for elasticity.

⏳ Reliability & Durability

Ensure uptime and no data loss through redundancy and failover. Balance cost vs. risk—design for resilience within reason.

🗃 Payload

Let's understand data characteristics:

- Kind: tabular, image, video, text

- Shape: dimensions like rows/columns or RGB pixels

- Size: total bytes; may need to chunk or compress

- Schema: field types and structure

- Metadata: context and descriptors for your data

Push vs. Pull vs. Poll

- Push: Source sends data to the pipeline

- Pull: System fetches from the source

- Poll: Regular checks for updates, then pulls

And here are some additional insight.

🔄 Streaming + Batch Coexist

Even with real-time ingestion, batch steps are common (e.g., model training, reports). Expect a hybrid approach.

🧱 Schema Awareness

Schemas change—new columns, types, or renames can silently break pipelines. Use schema registries to version and manage schemas reliably.

🗂️ Metadata Mattera

Without rich metadata, raw data can become a data swamp. Proper tagging and descriptions are critical for usability.

Batch Ingestion

If we went with batch way, here are some things to keep in mind. Batch ingestion moves data in bulk, usually based on a time interval or data size. It’s widely used in traditional ETL and for transferring data from stream processors to long-term storage like data lakes.

Snapshot vs. Differential Extraction

- Snapshot: Captures the full state each time. Simple but storage-heavy.

- Differential: Ingests only changes since the last read. More efficient.

File-Based Export and Ingestion

- Source systems export data as files (e.g., CSV, Parquet), then push to the target.

- Avoids direct access to sensitive databases.

- Exchange methods: S3, SFTP, EDI, SCP.

ETL vs. ELT

We defined ETL before. In ELT the definition is as follows:

- Extract: Pull data from various source systems (e.g., databases, APIs, logs).

- Load: Move the raw data directly into a central data store (like a cloud data warehouse or data lake).

- Transform: Perform data cleaning, enrichment, and modeling after the data is loaded—within the storage system itself.

Choose based on system capabilities and transformation complexity.

📥 Inserts, Updates, and Batch Size

- Avoid many small inserts—use bulk operations for better performance.

- Some systems (like Druid, Pinot) handle fast inserts well.

- Columnar databases (e.g., BigQuery) prefer larger batch loads over frequent single-row inserts.

- Understand how your target system handles updates and file creation.

🔄 Data Migration

Large migrations (TBs+) involve moving full tables or entire systems.

Key challenges are:

-

Schema compatibility (e.g., SQL Server → Snowflake)

-

Moving pipeline connections to the new environment

Use staging via object storage and test sample loads before full migration. Also consider migration tools instead of writing from scratch.

📨 Message and Stream Ingestion

Event-based ingestion is common in modern architectures. This section covers best practices and challenges to watch for when working with streaming data.

🧬 Schema Evolution

Schema changes (added fields, type changes) can break pipelines.

Here is what you can do:

- Use schema registries to version schemas.

- Set up dead-letter queues for unprocessable events.

- Communicate with upstream teams about upcoming changes.

🕓 Late-Arriving Data

- Some events arrive later than expected due to network delays or offline devices.

- Always distinguish event time from ingestion time.

- Define cutoff rules for how long you will accept late data.

🔁 Ordering & Duplicate Delivery

- Distributed systems can cause out-of-order and duplicate messages.

- Most systems (e.g., Kafka) guarantee at-least-once delivery.

- Build systems that can handle duplicates gracefully (e.g., idempotent processing). 🎉

⏪ Replay

Replay lets you reprocess historical events within a time range.

- Platforms like Kafka, Kinesis, and Pub/Sub support this.

- This is really useful for recovery, debugging, or rebuilding pipelines.

⏳ Time to Live (TTL)

TTL defines how long events are retained before being discarded. It's the maximum message retention time, which is helpful to reduce backpressure.

Short TTLs can cause data loss; long TTLs can create backlogs.

Examples:

- Pub/Sub: up to 7 days

- Kinesis: up to 365 days

- Kafka: configurable, even indefinite with object storage

📏 Message Size

Be mindful of max size limits:

🧯 Error Handling & Dead-Letter Queues

Invalid or oversized messages should be routed to a dead-letter queue.

- This prevents bad events from blocking pipeline processing.

- Allows investigation and optional reprocessing after fixes.

🔄 Consumer Models: Pull vs. Push

Pull is default for data engineering; push is used for specialized needs.

- Pull: Consumers fetch data from a topic (Kafka, Kinesis).

- Push: Stream pushes data to a listener (Pub/Sub, RabbitMQ).

🌍 Ingestion Location & Latency

- Ingesting data close to where it's generated reduces latency and bandwidth cost.

- Multiregional setups improve resilience but increase complexity and egress cost.

- Balance latency, cost, and performance carefully.

📥 Ways to Ingest Data

There are many ways to ingest data—each with its own trade-offs depending on the source system, use case, and infrastructure setup.

🧩 Direct Database Connections (JDBC/ODBC)

JDBC/ODBC are standard interfaces for pulling data directly from databases.

JDBC is Java-native and widely portable; ODBC is system-specific. These connections can be parallelized for performance but are row-based and struggle with nested/columnar data.

Many modern systems now favor native file export (e.g., Parquet) or REST APIs instead.

🔄 Change Data Capture (CDC)

Here are some quick definitions on CDC:

- Batch CDC: Queries updated records since the last read using timestamps.

- Continuous CDC: Uses database logs to stream all changes in near real-time.

- CDC supports real-time replication and analytics but must be carefully managed to avoid overloading the source.

- Synchronous replication keeps replicas tightly synced; asynchronous CDC offers more flexibility.

🌐 APIs

APIs are a common ingestion method from external systems.

- Use client libraries, connector platforms, or data sharing features to avoid building everything from scratch.

- For unsupported APIs, follow best practices for custom connectors and use orchestration tools for reliability.

📨 Message Queues & Event Streams

Use systems like Kafka, Kinesis, or Pub/Sub to ingest real-time event data.

- Queues are transient (message disappears after read); streams persist and support replays, joins, and aggregations.

Design for low latency, high throughput, and consider autoscaling or managed services to reduce ops burden.

🔌 Managed Data Connectors

Services like Fivetran, Airbyte, and Stitch provide plug-and-play connectors.

- These services manage syncs, retries, schema detection, and alerting.

- This makes them ideal for reducing boilerplate and saving engineering time.

🪣 Object Storage

Object storage (e.g., S3, GCS, Azure Blob) is great for moving files between teams and systems.

Use signed URLs for temporary access and treat object stores as secure staging zones for data.

💾 EDI (Electronic Data Interchange)

This is a legacy format still common in business environments.

- Automate handling via email ingestion, file drops, or intermediate object storage when modern APIs aren’t available.

📤 File Exports from Databases

Large exports put load on source systems—use read replicas or key-based partitioning for efficiency.

Modern cloud data warehouses support direct export to object storage in formats like Parquet or ORC.

🧾 File Formats & Considerations

Avoid CSV when possible due to its lack of schema, support for nested data, and error-prone behavior.

Prefer Parquet, ORC, Avro, Arrow, JSON—which support schema and complex structures.

💻 Shell, SSH, SCP, and SFTP

Shell scripts and CLI tools still play a big role in scripting ingestion pipelines.

- Use SSH tunneling for secure access to remote databases.

- SFTP/SCP are often used for legacy integrations or working with partner systems.

📡 Webhooks

Webhooks are "Reverse API" where the data provider pushes data to your service.

- Typically used for event-based data (e.g., Stripe, GitHub).

- Build reliable ingestion using serverless functions, queues, and stream processors.

🌐 Web Interfaces & Scraping

- Some SaaS tools still require manual download via a browser.

- Web scraping can be used for unstructured data extraction, but comes with ethical, legal, and operational challenges.

🚚 Transfer Appliances

- For large-scale migrations (100 TB+), physical data transfer appliances like AWS Snowball are used.

- Faster and cheaper than network transfer for petabyte-scale data moves.

🤝 Data Sharing

Platforms like Snowflake, BigQuery, Redshift, and S3 allow read-only data sharing.

- This is useful for integrating third-party or vendor-provided datasets into your analytics without owning the storage.

Summary 🥳

Here are some quotes from the book.

Moving data introduces security vulnerabilities because you have to transfer data between locations. Data that needs to move within your VPC should use secure endpoints and never leave the confines of the VPC.

Do not collect the data you don't need. Data cannot leak if it is never collected.

My summary is down below:

Ingestion is the stage in the data engineering lifecycle where raw data is moved from source systems into storage or processing systems.

Data can be ingested in batch or streaming modes, depending on the use case. Batch ingestion processes large chunks of data at set intervals or based on file size, making it ideal for daily reports or large-scale migrations. Streaming ingestion, on the other hand, continuously processes data as it arrives, making it suitable for real-time applications like IoT, event tracking, or transaction streams.

Designing ingestion systems involves careful consideration of factors like bounded vs. unbounded data, frequency, serialization, throughput, reliability, and the push/pull method of data retrieval.

Ingestion isn’t just about moving data—it’s about understanding the shape, schema, and sensitivity of that data to ensure it's usable downstream.

As Data Engineers we must track metadata, consider ingestion frequency vs. transformation frequency, and apply best practices for security, compliance, and cost.

We should also stay flexible: even legacy methods like EDI or manual downloads may still be part of real-world workflows.

The key is to choose ingestion patterns that match the needs of the business while staying robust, scalable, and future-proof.

8. Queries, Modeling, and Transformation 🪇

Now we'll learn how to make data useful. 🥳

Queries

Queries are at the core of data engineering and data analysis, enabling users to interact with, manipulate, and retrieve data.

Just to paint a picture, here is an example query:

SELECT name, age

FROM df

WHERE city = 'LA' AND age > 27;

Here is a complete example in Python:

import pandas as pd

import duckdb

# Create a sample DataFrame

data = {

'id': [1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

'name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie', 'David', 'Eva'],

'age': [25, 30, 35, 40, 28],

'city': ['NY', 'LA', 'NY', 'SF', 'LA']

}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

# Run SQL query: Get users from LA older than 27

result = duckdb.query("""

SELECT name, age

FROM df

WHERE city = 'LA' AND age > 27

""").to_df()

print(result)

# name age

# 0 Bob 30

Structured Query Language (SQL) is commonly used for querying tabular and semistructured data.

A query may read data (SELECT), modify it (INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE), or control access (GRANT, REVOKE).

Under the hood, a query goes through parsing, compilation to bytecode, optimization, and execution.

Various query languages (DML, DDL, DCL, TCL) are used to define and manipulate data and database objects, manage access, and control transactions for consistency and reliability.

To improve query performance, data engineers must understand the role of the query optimizer and write efficient queries. Strategies include optimizing joins, using prejoined tables or materialized views, leveraging indexes and partitioning, and avoiding full table scans.

We should monitor execution plans, system resource usage, and take advantage of query caching. Managing commits properly and vacuuming dead records are essential to maintain database performance. Understanding the consistency models of databases (e.g., ACID, eventual consistency) ensures reliable query results.

Streaming queries differ from batch queries, requiring real-time strategies such as session, fixed-time, or sliding windows.

Watermarks are used to handle late-arriving data, while triggers enable event-driven processing.

Combining streams with batch data, enriching events, or joining multiple streams adds complexity but unlocks deeper insights.

Technologies like Kafka, Flink, and Spark are essential for such patterns. Modern architectures like Kappa treat streaming logs as first-class data stores, enabling analytics on both recent and historical data with minimal latency.

Data Modeling

Data modeling is a foundational practice in data engineering that ensures data structures reflect business needs and logic. A data model shows how data relates to real world.

Despite its long-standing history, it has often been overlooked, especially with the rise of big data and NoSQL systems.

Today, there's a renewed focus on data modeling as companies recognize the importance of structured data for quality, governance, and decision-making.

A good data model aligns with business outcomes, supports consistent definitions (like what qualifies as a "customer"), and provides a scalable framework for analytics.

Modeling typically progresses from conceptual (business rules), to logical (types and keys), to physical (actual database schemas), and always considers the grain (resolution which data is stored and queried) of data.

A normalized model avoids redundancy and maintains data integrity. The first three normal forms (1NF, 2NF, 3NF) establish increasingly strict rules for structuring tables. While normalization reduces duplication, denormalization—often found in analytical or OLAP systems—can improve performance.